In one of my earlier blog posts, Tolerance for Failure, I noted that having an appropriate tolerance for failure from your team is necessary to promote a culture of innovation. Of course, there are many other things that an organization must have besides the willingness to allow employees to stretch. One of the more significant items is the capacity for innovation.

Innovation comes in many sizes, as do organizations. Having the capacity to allow innovation is not related to the size of the organization. Nor is it related to having a dedicated research department, process teams, etc. Small, incremental innovation has come from the freedom to effect change that is somewhat outside of the normal expectations of the work to be accomplished. This freedom comes from having a bit of slack in the day to perform outside of the box.

Tom DeMarco says that Slack is the “degree of freedom required to effect change. Slack is the natural enemy of efficiency, and efficiency is the natural enemy of slack.” Unfortunately, a lot of organizations are systematically eradicating slack in the pursuit of efficiency. With the goal of being ever more efficient, we’ve converted personnel resources into a commodity to be managed. We’ve leaned down the organization to do more with less. We’ve implemented matrix organizations to gain further efficiencies from fungible employees. Each of these reduces or outright eliminates any slack that could have allowed for experimentation and innovation.

I’ve found that engineering organizations are no different, especially for those with projects that have significant front-end effort requirements for design and testing prior to product sales. Engineering accounting practices for these project-based organizations are moving towards absorption costing and the capitalization of engineering effort rather than treating engineering costs as overhead expenses, as was mainly done in the past. While this does make the financials look better, it puts a direct cost burden to the project on each hour of engineering effort for that project. As a result, effort that doesn’t directly and efficiently apply to the project is discouraged by the project managers as it adversely affects the project efficiency of each effort hour and raises the project cost.

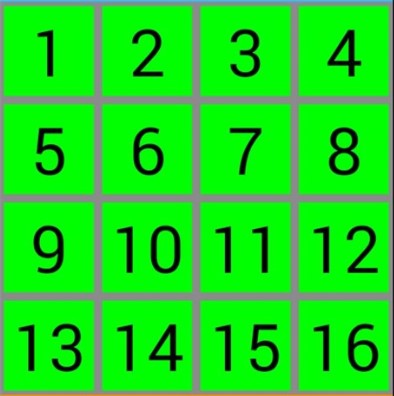

How do these organizations then innovate? For some, especially the smaller ones, they don’t. Consider the 15 tile sliding tile game.

Plugging a 16th tile into the game increases efficiency by using the wasted space. But now with no open space, it is impossible to rearrange the tiles. The organization of the tiles is stagnant. Would the organization be better if it counted down from 16? Went down the column first instead of across the rows? This organization may never know as they no longer have any slack for experimentation and innovation. Additionally, if the organization is smaller or in an industry with narrow profit margins, it likely doesn’t have resources dedicated to process or product innovation. These organizations need slack to have the capacity for innovation.

The old saw about doing the same thing and expecting different results does apply to being more effective. Slack is a way to invest in change to have the necessary capacity for innovation.

Stay tuned….